The other day at a restaurant, I overheard a guy expressing doubts to his friend about moving away from family. His friend offered a simple piece of advice: “Just do what’s best for you. Only you know what that is. If you don’t, you may regret it.”

Not long after, I stumbled upon another opinion echoing similar advice.

When I hear these takes, I can't help but think to myself: “What a wonderful way to end up alone,” and “What makes you so sure that you know what's truly best for you? You've managed to ultimately discover what's truly best!? Ah, but it is only relevant to you, you say? How disappointing—what are we supposed to do with that? Oh, I can find out for myself, you say? But how can I share it with others if it’s only available to me? Wouldn’t I want to share what was truly best if it truly was what was truly best!? Ah, right. It’s not about others—it’s about me.”

Which left me wondering: Why does self-centeredness seem so widespread in society? Perhaps it’s a reflection of a materialistic economy that has more to gain if consumers worship themselves, one might say. Or, says another, perhaps we're spreading ourselves too thin: with excessive work, sprawled suburbs and soaring sky-rises, or high-breadth communication tech that provokes low-depth relationships.

These all seem to play a role. But I’ll argue something deeper is at play—something buried beneath biology, philosophy, art, and mythology, waiting to be unearthed. That is what we’ll be doing today. Yet, for reasons that will soon become apparent, our dis-coveries won’t be so straightforward.

Among our first discoveries will be that you have good reason to be self-centered, and so you will have good reason to resist ideas that threaten your self-centeredness, like the ones proposed in this essay. But, as the title suggests, I'm nevertheless going to try to open you to the idea that You're not as important as you think you are.

Try to keep in mind that this doesn't mean you aren't important.

You are.

That's why I've written this.

“Humility is the most difficult of all virtues to achieve; nothing dies harder than the desire to think well of oneself.”

— T. S. Eliot

Three to four billion years ago, vital patterns arose that found themselves worth preserving, and so adapted themselves to enable that preservation. Encoded in the genotype and expressed through the phenotype, a subjective sense of self began to take shape.

We are here today because our forebears found it important to find themselves important. Without that, they wouldn't have foraged for food, evaded predators, or procreated. You and I are extensions of these self-sustaining patterns—patterns that endure because we have, in some way, deemed ourselves worthy of preservation. Thus underlying each of our individual behaviors lies the subtle assumption that I am the most important being to grace this planet.

And yet competition depends on collaboration. A creature’s sense of importance must extend outwards in time and space if it hopes to reproduce, as with parents and their children or celibate worker bees and their colony. Though it is still the genetic stars aligning in these cases, entwining the self with the survival and reproduction of kin. In eusocial insects, the hive thrives because every member plays a role in maintaining the genetic lineage, even for those that are celibate. In mammals, attachment behaviors in parents ensure that their offspring reach adulthood. But, whether through direct survival or through kin selection, self-importance remains engrained within the structures and behaviors that were deemed worth keeping.

The dynamics of importance nevertheless get quite interesting with us humans, involving a blossoming blend of individual and social interest. We are not just shaped by immediate survival pressures but by layers of cultural ideology. Unlike bees, we can adopt fictive kin—ideas that stir our sense of self beyond the genetic, and yet the core principle remains: we are drawn to preserve and perpetuate whatever feels vital to our sense of self, whatever self that may be.

We'll revisit the delightful sparks that fly from the collision of individual and social interests later, and it will turn out that these sparks kindled the fire that cooked up this essay. For now, I think it's enough to say that life thinks highly of itself1—and for good reason.

To believe, or not to believe

Here's the issue: the self-sustaining assumption that I am the most important being on this planet must be built upon fallacy, because there’s no way for all of us to be more important than everyone else. Either (1) one of us is truly the most important and the rest of us are wrong or (2) all of us are mistaken. The latter seems more likely to me.

Yet, kernels of truth often lay wrapped within lies. In fact, it is only by grace of this lie that we can even recognize it as a lie—for it is this very lie that sustains us. Illusion is the thing that allows us to discern illusion. Consciousness itself even functions like an artistic display, drawing us into its vision of the world while diverting our attention away from the subconscious brushstrokes that paint it. But if we convince ourselves that our consciousness is lying to us, we ought to be careful about believing it.

Consider a fine gentleman approaches you on the street and declares the following:

"I am lying."

Should you believe him? If (1) he is lying, then he would be telling the truth (i.e., not lying), except the statement being true would confirm he is lying. If (2) he is not lying, then he's lying about lying, a double negation that brings us back to him telling the truth. This is the liar’s paradox, a self-consuming statement that collapses under the weight of its own contradiction.

What I'm trying to illustrate with all this illusion talk is the tangled relationship between truth and falsehood. What I’m not saying is that everything’s false—falsehood itself requires some truth against which it can be contrasted.

The more we treat truth or falsehood as absolutes, the further we stumble into contradiction. The unwavering doubter, for instance, who treats falsehood as absolute, risks tumbling into nihilism where (he thinks) nothing matters. But even absolute doubt must stand on something—after all, “a doubt that doubted everything would not be a doubt” (Wittgenstein, On Certainty). And so, in his refusal to believe, the doubter inevitably believes in his refusal to believe, leaving him in a world that whispers to him, "I am lying." Uh oh...

Tragically, the unwavering doubter becomes what he most despises: the unwavering believer, who, convinced she's pointing at the ultimate truth, misses the point that she is prone to missing the point. Unwavering belief offers the same false promise of simplicity as unwavering doubt, and both are unbelievably and undoubtedly static and lifeless—it is in their wavering that the flames of faith are fanned, not in doubt or belief themselves.

Now, when an unwavering believer's claims to truth are reinforced by a higher authority—be it an ideology, or nation, or a deity—things get more interesting. More on this later.

Impressive

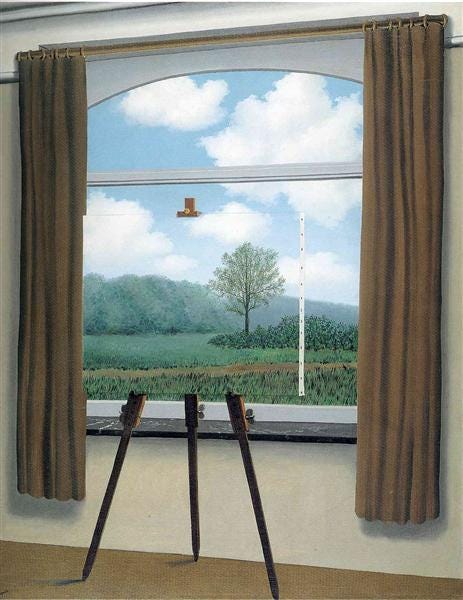

Picasso once described art as a lie that helps us see the truth, an observation with roots reaching back as far as the fourth century BCE. In The Republic, Plato, who was wary of the illusive nature of art, nevertheless acknowledged that he thought promoting social harmony would require persuading ignorant masses toward virtue through the use of what he called a Noble Lie: an invented myth that, while not an actual historical truth, would orient the masses toward higher ideals that fostered cohesion, stability, and justice.

Another striking example of truth enshrined in mystery can be found in the ancient Egyptian goddess, Isis. Her association with mystery is most vividly illustrated in veiled depictions of her, traced back to the first century CE in the city of Sais2, where a statue of her once bore the inscription:

I am that which was and is and Will ever be, and no mortal has yet Lifted the veil which covers me

I suspect the unwavering believer and her brother, the doubter—who both claim to have dis-covered the ultimate truth or untruth—would struggle dis-covering Isis. Much like the veil impressing itself upon Isis' face, we conceive of reality through impressions. We do not encounter nature directly; we grasp it through the veil of our senses—through touch, taste, smell, sound, sight, and thought. When we feel a physical object, we apprehend not the thing itself, but rather our response to the energetic and chemical signals that are impressed upon our nervous system by the object. Our sensory reconstructions feel so real, much like how we can get a sense of the contours of Isis’ face beneath her veil, and yet they must always be, to some extent, surreal.

This paradox extends beyond the senses. As Einstein put it, "As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they are not reality." Certainty demands abstraction, yet reality resists confinement, forever slipping past our conceptual frameworks. Reality, like Isis, remains veiled. And yet, it is this very limitation that fuels our pursuit of knowledge, compelling us to lift veil after veil.

Life depends on mystery, consuming it as a fire does its fuel. Life’s movement is imbued with purpose by this very yearning, this ceaseless churning of mystery, where one veil is removed only to reveal another. As we'll come to dis-cover, perpetual revelation plays a key role in revealing to us that we are not as important as we think we are.

Ego’s offspring

Earlier, we noted that biological motives boil down to something like: I'd like us to sustain ourselves over time, so let’s adjust our understanding of the world in ways that allow us to hold ourselves together and flourish. But self-preservation necessarily distorts perception, for the self must organize a world in which it can persist, whatever self that may be. Think of the organizations who refuse to accept evidence that contradicts their theories, or the mother convinced her child can do no wrong. Self-interest births illusion.

The interplay between illusion and self-interest is beautifully embodied in the father-son duo, Ravana and Indrajit, from the Hindu epic Ramayana. The hero, Rama, is a virtuous and dutiful prince who also happens to be a reincarnation of Vishnu: the deity of truth, harmony, and preservation. Sita, Rama's wife, ends up being abducted by Ravana, a powerful demon king whose spiritual devotion in his youth granted him immortality against gods. Rama then gathers an army and travels to the demon kingdom to rescue Sita, and although Ravana is given many opportunities to return Sita, his pride cannot allow it.

Ravana had ten heads and twenty arms. On the one hand, his heads symbolize profound intellect, his arms skill in warfare. On the other nineteen, they symbolize excess. When we think ourselves as more important than we are, it is as if we believe we have those ten heads and forget we only have the one. Ravana also reminds us that intellect and skill are not virtues in themselves. Without a radiating love, they become tools for domination. The sharpest minds, if guided by ambition rather than wisdom, can build both wonders and horrors. After all, it is immense intellect and skill, coupled with national ambition, that developed and deployed nuclear weapons.

Where there is excess, there is illusion. And it so happens that Ravana's eldest son, Indrajit, was a master of maya (illusion), capable of fighting invisibly and conjuring bewildering false images. Here we find the mythological expression of biological delusion: a pinnacle of self-importance begetting a master of illusion. A striking parallel to this theme can also be found in Dante’s Inferno, where, at the bottom of hell, Dante and Virgil encounter a three-headed Satan gnawing on great masters of deception: Judas (betrayer of Jesus), and Brutus and Cassius (betrayers of Caesar).

In Hindu philosophy, among the most misleading forms of maya are:

Permanence: The illusion that the material world is unchanging, rather than in constant flux of integration (birth) and disintegration (death).

Independence: The illusion that we exist as separate from our surroundings, rather than interwoven with them.

Satisfaction: The illusion that fulfilling a desire will bring lasting contentment, rather than giving rise to new desires.

Ravana is undone by all three. First, he believes himself immortal (permanence), forgetting that, while he is immune to gods, he is vulnerable to mortals. Second, he believes his power makes him entirely self-sufficient (independence), and so he rejects wise counsel from his people to return Sita and ask for forgiveness. And third, he believes that possessing Sita will bring him ultimate fulfillment (satisfaction), but his insatiable desire instead leads to ruin.

Playful persuasion

Maya, in its original sense, meant something like "magic creative power." And magic can both mislead and reveal. If we are draped in illusion, how do we know whether the spell of maya guides us toward truth or leads us astray? This tension brings us to two opposing yet necessary forces: domination and revelation.

The three misleading forms of maya—permanence, independence, and satisfaction—lead to avidya, or ignorance. This ignorance is maintained through domination, where sovereignty (independent eternity) and the promise of eternal delight are established. Anything that threatens the reign of ignorance is hastily smothered, lest its comforting veil be burned away by flames of truth. Yet wisdom, too, requires establishment, for without structure wisdom has no home.3 Domination, then, is neither good nor bad; rather, it depends on what it serves.

Revelation clears the illusions that domination establishes, giving truth room to breathe. To understand revelatory illusion, we may turn to another Hindu concept: lila, or divine play. At its core, lila leads to the dramatic revelation of impermanence, interdependence, and the insatiability of selfish desire, leading one to vidya, or true knowledge. We see lila in the mischievous antics of Krishna, another reincarnation of Vishnu. When a young Krishna was accused of eating dirt and his foster mother Yashoda asked him to open his mouth, he revealed to her the universe within it. We find lila, too, in the parables and miracles of Jesus, his first miracle being especially playful: turning water into wine at a wedding.

At the heart of play lies voluntary surrender. Dogs at play, for instance, lower themselves into play posture as each surrender to a shared ideal: their play. But the moment one attempts to dominate the other, say by biting too hard, their partner shrieks and play grinds to a halt. Marriage offers a similar example: it thrives on a balance of freedom and surrender. Catholic teachings, for instance, ensure both bride and groom enter into marriage freely (voluntarily), offer themselves totally to one another (surrender), and commit faithfully to a union that is fruitful—one that generates more play. Once again, when a partner tries to dominate the other—to win the game because they believe they are more important than they are—they threaten to end the infinite game that marriage attempts to establish.

Revelation is frightening, requiring us to abandon comfortable beliefs—such as the belief that we are more important than we are—and trust instead in something beyond our grasp. And we are far more likely to surrender to that something if it’s playful. If you wish to slip past someone’s pride, best do it through artistry rather than force. As our noble liar put it: “A body that’s forced to work hard is never the worse for it, but a lesson forced on the soul is never retained. […] As you bring up these children of yours in their various subjects, best not to do it using force, but in the form of play.” (Plato, The Republic)

This is why art will never cease to play a central role in humanity’s moral unfolding—it lures us towards higher truths without us even realizing it. In his sprawling novel Ulysses, James Joyce wrote that “Art has to reveal to us ideas, formless spiritual essences. The supreme question about a work of art is out of how deep a life does it spring.” The deeper the life, the deeper the art; the deeper the art, the deeper the revelation; the deeper the revelation, the deeper the life…

This brings us to the tragedy of the individualistic mindset: there is no play.

Individualism builds something that builds nothing. It treats the self as most sacred, most true—yet play is impossible alone. It is a form of cowardice, hiding beneath a shallow veil that offers a delightful pocket of certainty, resisting revelations that may allow uncertainty to pour in. And so, illusions are mounted in defence, such as the argument that “ultimately, though, no one knows what is truly best for you but you”, just as Ravana relied on Indrajit’s magic to shield him from Rama (truth itself). But all illusions, no matter how cunning, eventually collapse before the weight of what is real.

Snakes and ladders

Having started with a stable biological base, then peppered upon it paradoxes and miraculous stories, I’d like to return to biology once more—this time with the late entomologist E. O. Wilson. Wilson studied eusocial insects (e.g., ants and bees) and was eventually persuaded by the theory of multi-level selection: the idea that natural selection operates simultaneously at different levels of biological organization, implying that, beneath every biological behavior, there lies a delicate tension between competition and collaboration that interweaves the fabric of our minds with minds within our ecological milieu.

Put more simply: an isolated egoist outcompetes an isolated altruist, but groups of altruists outcompete groups of egoists. Thriving—both individually and collectively—requires striking a balance between selfishness and selflessness, pride and humility, domination and revelation. If a group dominates its individuals, suppressing their ability to self-maintain, both perish. If individuals dominate their group, trust erodes, cohesion dissolves, and the group falls to more unified competitors. From this tension, E. O. Wilson drew a striking observation: what we call sin tends to benefit the individual at the expense of the group, while virtue often demands personal sacrifice in service of the whole.

We began with the observation that self-preservation fosters the illusion that I am more important than I truly am—and yet, it is this very illusion that allows me to exist. But now we’ve dis-covered that self-preservation operates hierarchically: groups organize themselves for group-preservation, insofar as groups offer their self-interested individuals security. Meaning, groups, too, have a biological incentive to believe that they are more important than they really are—and once again, it’s thanks to this illusion that we exist at all. Paradoxically, as members of groups, we thus also have a biological incentive—and, perhaps equivalently, a spiritual incentive—to believe that we are less important than we think we are, lest we harm the very groups on which our survival depends.4

And so here we are. We’ve peeled away the veil from the individual, only to reveal another hovering above the group. We’ve evolved from one illusion, only to arrive at another.

But is this illusion less pernicious? If it elevates us from the belief that I am the most important to the belief that others—at least within my group—are just as important as me, then perhaps we are approaching something closer to truth. The great projects of science and religion, at their best, are themselves institutions of humility, engaged in far more sophisticated attempts to do what I have attempted in this essay: to convince you that you aren’t as important as you think you are. And I think we would do well to heed their advice.

So, maybe we don’t know what’s truly best for us. And maybe we’ll be a little easier on ourselves if we admit it. Maybe opening ourselves to help—to family, friends, and to enduring wisdom traditions—will make life more bearable. Maybe, instead of shrinking into ourselves, we should expand beyond ourselves—into something richer, more interconnected, more alive.

Maybe we’re not as important as we think we are.

And maybe that’s what makes us important after all.

But what about those of us who think lowly of ourselves? Well, we're still thinking about ourselves, aren't we?

It has been contended that this statue was actually of Neith, another ancient Egyptian deity who was said to be the creator of the world and mother of the sun god, Ra. For the purpose of this discussion it doesn't matter which goddess we go with—what matters is whether she helps us see the truth.

Think of the genotype: a structure that, while being modifyable (via gradual revelation, perhaps?), requires domination to establish its biochemical structure.

Some say these sorts of explanations drain the meaning and beauty out of human nature. But that doesn’t seem right to me. Striving to understand human nature, and its stories laden with villanous betrayals and heroic sacrifices, doesn’t make it any less beautiful or any less meaningful. It’s my sense that these collaborative connections we have with these larger groups—whether those groups encompass people, beings, or the cosmos—are what allow us to detect meaning and beauty in the first place, and breach the threshold of the spiritual.

Another couple of thought I figured I’d put here:

1) when I hear that “we’re not as important as we think we are” - I see two directions to move. Either lowering our own perceived importance, or raising the importance of all else around (or perhaps some of both). The first to me seems connected to nihilism where nothing matters where the latter acknowledges that everything matters. In elevating whats around, I see connection to an indigenous view of the world and ideas of animism.

Does the lion eat the gazelle because it feels it’s more important, or as a necessary part in keeping everything moving? I perceive a division between biology and spirituality here.

I’m currently reading “Braiding Sweetgrass” where the author invites the reader to see the natural world as important and conscious in its own way.

2) Your post had me thinking about Indra’s net. Each individual exists as a jewel as a node in the net, and reflects every other node. In this sense, each node is important to the whole as any action will resonate throughout the whole web - it’s just that there is no hierarchy of importance. Can we see it as the paradox that “we’re just as important as we make everything else out to be”?

Great post John!

I’m still left with a question - what do we do with the paradox that doing more for our community makes us more important?

If I live altruistically, my community will benefit from my actions which will also make me more important. Does it also matter if this happens deliberately with importance as a goal or unintentionally? I see Oskar Schindler and Rosa Parks as examples of the latter